I’ve been thinking about information theory, entropy, and passphrases for a couple of months now. I’ve been particularly interested in using random passphrases as passwords. An example of one of these passphrases would be “stamina turret backlands ruby”. The words have to be as purely random as possible – using your four dogs’ names is not nearly as strong as a password, as an attacker would likely guess that relatively early.

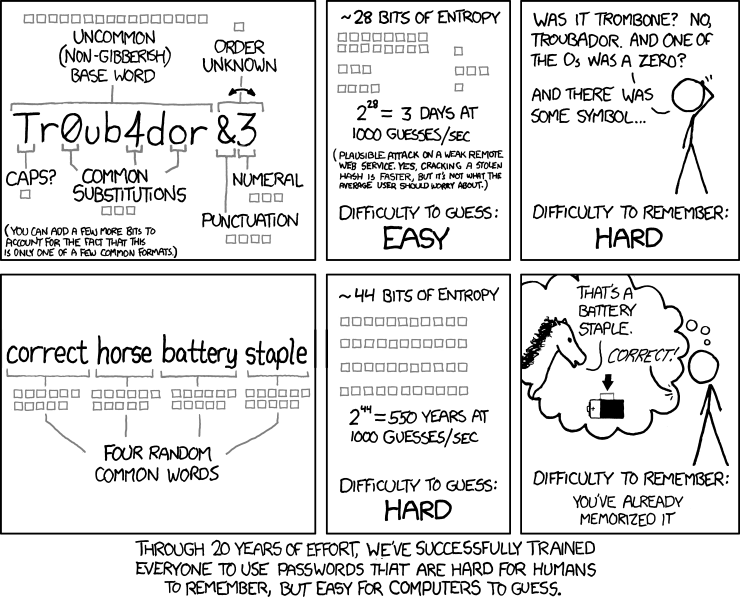

If you chose the words randomly from a list (more on these lists below), the resulting passphrase is actually mathematically pretty strong compared to passwords you may have be trained to think are strong. There’s a classic xkcd comic illustrating this point:

Crucially, even if an attacker knows what list you used and how many words long your passphrase, there’s just too many possible combinations to guess.

And of course, four words are surprisingly easy for a human to memorize. A long-lasting turret planted in ruby-filled backlands is an easier story to remember than “V7L8HQu6K”, which has about the same amount of strength according to the password strength estimator zxcvbn.

The fact that these phrases take advantage of humans’ ability to create a story to remember the phrase seems notable to me. There’s something fundamentally human about creating and carrying stories with us. If using complex passwords is a battle between human and machine (say a password-cracking GPU), we need to use every advantage humans have over computers. It’s a peculiar inversion of Licklider’s “Man-Computer Symbiosis”, a revolt of sorts against the frightening and (I would argue) underestimated capacity of modern computers (again, watch Computerphile’s video on password cracking or check out Weapons of Math Destruction).

A Question

Earlier this year I watched this Computerphile video called “Diceware & Passwords”, which offers a nice introduction to a method of generating these random passphrases using dice. About 8 minutes in the presenter, Dr. Mike Pound, explains something that perked my ears up: He explained that you need spaces (or other punctuation) in between the words because “sometimes you might accidentally join two words together and they’d actually be a different word on their and in which case your [phrase] goes down to four words.”

Here’s the hypothetical he’s describing: What if we just mashed our words together, so instead of “casket-stoppage-desk-top” we just used “casketstoppagedesktop” as our password. The problem here is that, if “desktop” is also a word on your word list (and thus the attacker’s list, given our assumptions above), this passphrase is only a three word phrase, which is notably weaker than a four-word phrase. The user thinks they have the security of a four-word phrase, when they really only have three. Note that this would only happen in rare cases when two words that make a compound word that’s on list are right next to each other, and, of course, the user chooses not put anything between the words. It’s important to note that if there is punctuation between the words, this problem does not exist.

I knew that my chosen password manager, KeePassXC, allows users to generate passphrases with punctuation between words or without punctuation. (Below is an example with hyphens between words.)

When generating passphrases, I generally put a hyphen or space between the words (as seen in the GIF), but what if for some I had not, and one of them had one of the “collisions” that Dr. Pound describes in the video? More broadly, was there a way to check or edit word lists in order to make this problem impossible (and thus more foolproof?).

Prefix Codes

Apparently the traditional way of preventing these sorts of issues is to ensure that your “code system” has the “prefix property”, and thus would be referred to a prefix code.

A prefix code is a type of code system (typically a variable-length code) distinguished by its possession of the “prefix property”, which requires that there is no whole code word in the system that is a prefix (initial segment) of any other code word in the system. For example, a code with code words {9, 55} has the prefix property; a code consisting of {9, 5, 59, 55} does not, because “5” is a prefix of “59” and also of “55”. A prefix code is a uniquely decodable code: given a complete and accurate sequence, a receiver can identify each word without requiring a special marker between words. However, there are uniquely decodable codes that are not prefix codes; for instance, the reverse of a prefix code is still uniquely decodable (it is a suffix code), but it is not necessarily a prefix code.

This “prefix code” idea is more broad than the task I set out for myself – it’s a possible property of all code systems, not just diceware passphrases.

I later learned that the EFF, in making their long word list for generating random passphrases, “ensured that no word is an exact prefix of any other word,” which seems like exactly the definition of a prefix code.

The process I outline below was undertaken before I understood that “[ensuring] that no word is an exact prefix of any other word” also ensured compound-safety as I came to define it. For example, this diceware tool has a specific section in its README dedicated to warning users about “the prefix code problem”.

With the benefit of hindsight, I’ll say that my work below was an attempt to create a program that would make a given word list compound-safe more efficiently that simply making it a prefix code. By more efficient I mean that it could remove fewer words from the original, compound-unsafe list than removing words that are exact prefixes of other words, thus providing more bits of entropy per word. More on this hypothesis below.

Update from 2021: If you just want to remove all prefix words from a word list, check out my newer project, Tidy.

Just a note: Thanks to phoerious for leaving an extremely illuminating comment on the original version of this blog post (reproduced below).

First Results

By the end of February I had slapped together a quick Rust script in an attempt to answer this question. I was specifically interested in testing the word list that KeePassXC uses, namely the EFF long word list, which is 7,776 words long.

I’m new to Rust, so I had to use poor logic to get the program to work: It mashes every pair of words together, then check that “mashed” word is one of the other 7,774 words on the list. Since this program had to run 7776^2 checks against the list, it was pretty slow (I also didn’t know to run Rust as a release rather than in debug mode). But 11 hours later the program informed be that it found no “bad words” in the EFF long word list. This means that, even without punctuation between words, there’s no way to encounter the problem described by Dr. Pound.

Taking it a Step Further: Compound Safety

I let this idea sit for a while, but eventually I made some more observations and even invented a term to help me get my head around this problem of weakness in passphrases without punctuation between words. There are of course other word lists that are used to generate these passphrases, and some of them, unlike the EFF list, might be susceptible to this issue!

OK, so here’s a definition for us. A passphrase word list is “compound-safe” (that is, it’s safe to join words without punctuation or spaces) if it…

-

does NOT contain any pairs of words that can be combined to make another word on the list. (We’ll call this a “compounding”)

-

does NOT contain any pairs of words that can be combined such that they can be guessed in two distinct ways within the same word-length space (We’ll call this a “problematic overlap”).

Number 1 is the Dr. Pound issue described above. Number 2 is new – it was suggested to me by a social media user.

An example of condition #1: If a word list included “under”, “dog”, and “underdog” as three separate words, it would NOT be compound-safe, since “under” and “dog” can be combined to make the word “underdog”. A user not using spaces between words might get a passphrase that included the character string “underdog” as two words, but a brute-force attack would guess it as one word. Therefore this word list would NOT be compound-safe. (I refer to this as a “compounding”.)

An example of condition #2: Let’s say a word list included “paper”, “paperboy”, “boyhood”, and “hood”. A user not using spaces between words might get the following two words next to each other in a passphrase: “paperboyhood”, which would be able to be brute-force guessed as both [paperboy][hood] and [paper][boyhood]. Therefore this word list would NOT be compound-safe. (I call this a “problematic overlap”.)

Another way to think about problematic overlaps: if, for every pair of words, you mash them together, there must be only ONE way to split them apart and make two words on the list.

My idea was that it would be useful to know, given a word list, if it is “compound-safe” or not. That is, is it safe to generate passphrases without punctuation between the words without fear of the two issues described above.

Just Tell Me About the Thing You Made

Compound Passphrase List Safety Checker is a command line tool written in Rust that takes a given word list and checks to see if it’s compound-safe, according to the two conditions above. If it is found to be safe, it simply exports the list as is. But if the tool finds compound-safe violations, it removes enough words for the list to be compound-safe. Since a longer list leads to “stronger” (read: higher entropy) passphrases, it attempts to remove the minimum number of words to make the outputted list compound-safe, however I have yet to spend a lot of time optimizing this.

Here’s the section of the README on how to use to tool to check a word list.

Update from 2021: I’ve improved and re-written this code as csafe. It does the same thing but better and faster.

Safe Enough?

I hadn’t thought of the second condition (“problematic overlaps”) until it was suggested to me by a Fediverse user. And even then it took me a sleepless night to understand it. My point being: there may well be other ways that putting random words together without punctuation to create passphrases can be problematic in terms of entropy and/or guessability. In other words, I don’t know if the edited lists outputted by this tool are actually safe enough to use without punctuation between words.

The 1Password List

The EFF long list is compound-safe even given the second, “problematic overlap” condition described above (again, phew/cool). However, I found the word list (named agile_words.txt in my project) used by the 1Password password manager is NOT compound-safe. PLEASE NOTE: this is NOT a security problem, since 1Password requires users put punctuation between the generated words. Let me say this again: This is not a security issue with 1Password.

I found 2,661 compound words (like “underdog”), made up of 1,511 unique single words (“under”, “dog”). The tool was able to remove just 498 of these single words to make compoundings impossible.

The tool also found 2,117 problematic overlaps in the 1Password list, and marked 2,117 words for removal.

All told, the tool removed 2,225 unique words from the 1Password list to make a new, compound-safe list. Thus my compound-safe version of the Agile list has 16,103 words, down from the original 18,328 words. With 16,103, each word from this list would add about 13.98 bits of entropy to a passphrase, compared to the original 1Password list, which adds about 14.16 bits. (2021 update: CSafe saves 16,789 words from this list.)

Now, listen, I don’t recommend you go download the 16,103 word list and start generating phrases without punctuation. I’m a social media editor, not a security researcher.

Again, with emphasis: 1Password’s software, as far as I know, does NOT allow users to generate random passphrases without punctuation or spaces between words. Users must choose to separate words with a period, hyphen, space, comma, or underscore. So these findings do NOT constitute a security issue with 1Password.

Back to my hypothesis

Now the question is: If take the 1Password list and remove all words that are exact prefixes of other words on the list, how many words would remain? To answer this question, I wrote a separate Rust script that did simply this. Fascinatingly, the “no-prefix” 1Password list has just 15,190 words. Each word from this list adds 13.89 bits of entropy.

This is fewer words and fewer entropy-per-word than my “compound safety” script preserves (16,103 words, good for 13.98 bits of entropy per word). Pretty cool!

It’s 100% possible that these “compound safe” lists that my script generates aren’t actually safe for use in random passphrases without spaces between words. For one obvious example, there could be problematic examples I haven’t thought of. So if you’re actually going to clean a word list, I’d probably advice you use Tidy or the no-prefix script rather than the compound safety script, mostly because that’s what the EFF did.

Toward a more theoretical understanding of compound safety

Given that my compound-safe 1Password list is longer than the no-prefix 1Password list, we can wonder: Is the no prefix-rule too strict? In other words, are there word lists that don’t satisfy the prefix rule but are compound-safe? I think my compound-safe version of the 1Password list is exactly this, but again, I don’t know if there are further conditions necessary to ensuring true compound-safety.

Also, relatedly, is it problematic that my compound-safe lists have words that are exact prefixes of other words that remain on the list?

At present I’m not sure why EFF fellow Joseph Bonneau avoided exact prefixes. But considering his extensive experience in this area I’d assume it was to avoid problems at least related to the one I’ve been describing. What I’m more interested in is understanding a more formal definition of what makes a good word list, and, if possible, developing a tool to check if a given list is safe to use in the most number of ways and contexts possible. Toward that end, I’d say my tool is a proof of concept at best.

Appendix A: How Often Are Non-Safe Passphrases Generated

As I note in the tool’s README, I don’t really know. I’m just not that strong at probability math. I appreciate any insight on this – and I’d be curious what an “acceptable” probability would be, if any.

Appendix B: A Practical Use?

KeePassXC still lets user generate phrases without punctuation, and it now also lets users use their own word list (source) (though it appears to be not very easy to do). This is certainly a nice feature, particularly for non-English speaking users. However I wonder if the lists added by users will be as carefully constructed as the EFF list. This tool could be used to “clean” lists before use (I have no reason to believe it wouldn’t work for languages other than English, assuming special characters are handled well). Or it could even be re-written in C++ and integrated into KeePassXC, to be run on any user-selected word list.

It may seem more practical to have a random passphrase generator like KeePassXC’s check individual generated passphrases for compound-safety (and maybe only when the user chooses to have no punctuation between words). But I think this would decrease the entropy-per-word of the passphrases in a complex, unintuitive way. But that’s just a guess really. Of course KeePassXC could also force users to use a word separator, like 1Password does.

Appendix C: Caveat about “Three-Word Compounding”

While we’ve explored “two-word compounding”, where two words are actually one, I accept that there is a possibility of a three-word compounding – where three words become two, or three words mashed together can be split in more than one way. No idea how likely that is, or how to efficiently check for that, but know that this tool does NOT currently check for this, and thus I can’t actually guarantee that the lists outputted by the tool are completely compound-safe.

Here is where the more-straightforward approach of eliminating all prefix words, to be safe, may be superior.

Appendix D: Preserving a comment left on the original version of this post

In case I move blog systems and lose my Disqus comments again, here is phoerious’s comment, referred to above, in full:

I think the whole matter becomes easier to grasp when you don’t think about it in terms of words, but in terms of pieces of information. Imagine a three-sided die with sides for “a”, “b”, and “ab”. The first two sides each have 0.5 bits of entropy, but the third side is redundant and adds no further information. A message “ab” is always “ab” no matter if it was created by one or two tosses. If we add a separator between code words, we artificially make “ab” distinguishable and the entropy per character rises to 0.52 bits. I say “artificially”, because it’s the same as if we replaced “ab” with a third code word “c”. But what do we do when we run out of unique characters? Then we have to use combinations, but must take some things into consideration if we don’t want to lose information (and therefore reduce entropy of the message). Here we come into the field of minimal prefix-free codes, also called Huffman coding or entropy coding. It’s the fundamental building block for compression, where we try to find a minimal code for a message given a certain alphabet. As an example, take an alphabet of three words, which we want to encode in binary. We only have 0 and 1 at our disposal, so we need to use combinations. We could naively encode them as 00, 01, and 10. But that is clearly over-encoded (two bits can encode four words). However, if we use variable-length codes 0, 1, and 10, we would need separators, otherwise we wouldn’t know if 010 is 0,1,0, or 0,10. Thus, we need a prefix-free code. Such a code would be 0, 10, 11. Here we have our prefect compromise between the number of encoding bits needed and unambiguity, i.e., we don’t lose any information.

I think at this point you can easily do the transfer back to word lists. Each word is a code word and we need them to be prefix-free to not lose information. Does it matter if “underdog” is an English word if only “under” and “dog” are on the list? No. All that matters is what else is on the list. The same is true for “underdog” and “dog”. As long as “under” is not a word on the list, we are fine.