Back in autumn of 2016 I read three books about technology that left a bit of mark on me: Coding Freedom, Code and Other Laws of Cyberspace, and The Cathedral and the Bazaar.

The *intro* of @BiellaColeman's 'Coding Freedom' quotes from Marx, Barthes(!) and Rilke(!!) as well as Richard Stallman, @StevenLevy, & xkcd

— Sam Schlinkert (@sts10) September 21, 2016

Broadly, all of them touch on the concept of “free software” or “open source software”. I put both of these in quotes because their exact definitions are still a bit fluid– for example, it’s still a bit of touchy subject as to whether they are the same concept or two distinct concepts– but to get us on the same page let’s quote the Wikipedia article on free software:

Free software or libre software is computer software distributed under terms that allow users to run the software for any purpose as well as to study, change, and distribute it and any adapted versions. Free software is a matter of liberty, not price: users —individually or in cooperation with computer programmers— are free to do what they want with their copies of a free software (including profiting from them) regardless of how much is paid to obtain the program. Computer programs are deemed free insofar as they give users (not just the developer) ultimate control over the first, thereby allowing them to control what their computers are programmed to do.

Blooming Most Recklessly

Coding Freedom, which is also available for free as a PDF, in particular gradually convinced me that there was something grand about using free software (like Firefox) and that, conversely, some real negatives to using proprietary software (like Microsoft Word).

But first, here are some of more obvious benefits of free software. First of all, the code is open source and thus is public, so anyone can read it and “fork” it in order to add features, find bugs (this is a particularly strong advantage for any software that has to handle secure data, like a password manager or secure messenger), or simply adapt the software to their individual needs.

The fact that the code is public and (legally and technically) free to be adapted also means that there’s no one company or person that can end the life of a piece of software – if there are other developers who want to pick a project up, they can. Or if one team of developers is taking the software down a path that some users don’t like, it can be “forked” to create a wholly new project (Neovim and KeePassXC are two such examples).

While Coleman is interested in those dynamics, her book gets at something a bit larger. Whereas companies make (most) proprietary software, she writes, people make free software, and often in their free time. This means they’re incentivized by something other than money, which turns out is a really good thing when it comes to writing software. As Coleman writes (page 120):

Over years of coding software with other developers in free software projects where discourses about liberty run rampant, many many developers come to view F/OSS as the apex of writing software… It has, they say, the necessary legal and material features that can induce as well as fertilize creative production. In contrast to the corporate sphere, the F/OSS domain is seen as establishing the freedom necessary to pursue personally defined technical interests in a way that draws on the resources and skills of other individuals who are chasing down their own interests… One developer told me during an interview that “managers […] decide the shape of the project,” while the F/OSS arena allows either the individual or collective of hackers to make the decision instead. F/OSS allows for technical sovereignty.

As software engineer Jessie Frazelle puts it, “As much as you think open source is all about the code, it’s really about the people.”

As much as you think open source is all about the code, it’s really about the people.

— jessie frazelle (@jessfraz) January 15, 2018

These hackers, as Coleman often refers to them, don’t want or need to sell you their product, or the new version of their product, or, crucially, any of their other products. They’re often making tools that they themselves need or want, and they share them. And through this process there is a sort of technical independence (Coleman 44) gained.

With the peskiness of money out of the way, and armed with modern technical and legal tools that allow for easy and fluid modification and accepted of new code to program (either to fix bugs or add new features), free software projects can take on a life of their own. Earlier in Coding Freedom, quoting another hacker (41):

The important difference for me is whether I come away feeling that I have created something of lasting intrinsic value or not… [most] often when I am done with corporate software, it’s dead, and when I am done with free software, it is alive.

If this reverence for free software wasn’t made clear from the above quotations, Coleman is more poetic in the beginning of her book (20):

The world of hacking, as is the case with many cultural worlds, is one of reckless blossoming, or in the words of Rilke: “Everything is blooming most recklessly; if it were voices instead of colors, there world be an unbelievable shrieking into the heart of the night.”

I have gotten to bloom some colors myself, albeit small ones; and some of my most significant didn’t even involve me writing code. As one example, here’s a bug report I wrote for my password manager, KeePassXC. I had only heard about the bug because an anonymous user had read my blog post on the program and contacted me describing a problem. I reproduced the problem he or she was having, and then wrote up the issue in the clearest way I could.

At first, two of the lead developers dismissed the bug as being impossible. But after a pretty substantial discussion in the comments, most of which I didn’t quite understand (I don’t even write C, the language KeePassXC is written in), it was eventually solved with two separate changes to the code (called “pull requests” in GitHub lingo), and when the new version of the software was released, every one got access to the improvements for zero dollars. It was a thrill.

Baby Steps

But could I, personally, switch to using open source software exclusively, not just my password manager? What other software was I using already that was open source? Were there any closed source programs I was using that did not have open alternatives? Maybe I’d love the open source alternatives.

At first I figured I’d do things like switch out closed source apps for open source alternatives: from Apple’s Mail to Thunderbird for example, and strive to use Mastodon, “The world’s largest free, open-source, decentralized microblogging network,” more and Twitter a bit less. I could try to switch from Microsoft Office to something like LibreOffice (though to be honest I don’t use Office much these days, and if I do Google Docs works fine for most of my needs). Even using Firefox rather than Chrome would count.

But eventually I realized that if I continued using macOS I would still be using a lot of closed source software as part of the operating system: the file manager, the calculator, the login system, etc. To solve this issue, I would have to leave macOS for an open source alternative– an open source operating system.

Coincidentally, my trusty MacBook Air had just had its fourth birthday and its 128GB flash hard drive was getting a bit cramped. I was also getting worried about upgrading it past macOS 10.10, as in my experience my Macs got a bit slower with with each OS upgrade beyond the first few. But I’d been using Apple computers since high school. Could I really not buy a MacBook? Could I leave Apple?

Why Not Another MacBook

After more than 500 days without an update (according to Bloomberg), Apple finally unveiled a new MacBook Pro in October of 2016. These new models introduced the Touch Bar and had either two or four Thunderbolt 3 ports.

Given my options as of fall 2017, if I were sticking with Apple I’d likely have gotten the 13” Touch Bar model with 16GB of RAM, 256GB of flash storage, and four Thunderbolt ports for $1,999. But a few things about it just didn’t feel right. It felt safe, in a bad way. MacOS feels tired; the Touch Bar a gimmick; and the 16 GB ceiling limiting.

The New MacBook Hardware

The Ports

I plug a lot of stuff into my laptop. When I’m at home I have an external keyboard, a mouse, a second monitor, speakers, and an external hard drive plugged in to my 2012 MacBook Air almost all of the time. This, in addition to the Mag-Safe power plug, occupies almost every port my Air has.

If I went with the MacBook Pro model that only has two Thunderbolt ports, that’d be one for power (we lose the convenience and safety of Mag-Safe) and another for everything else. Is there a single dongle that accepts two USB ports and a mini-display port or two for external monitors? Or would I have to pay up for the version with four ports?

Of course if I bought this 5K LG monitor for a cool $1,299.95 that Apple sells on its site, I’d get that monitor and power, plus it’d 3 extra Thunderbolt ports. But I don’t want to buy that particular monitor– I don’t need 5K resolution and I’ve already got a 27” Dell monitor that I use with a DVI-to-mini-Display Port converter, the updated version of which currently sells for $445.

In practice I think my new Mac would have come with a ticket to dongle city.

Apple's fastest growing product category. pic.twitter.com/d1sel4N5Yc

— Drew Breunig (@dbreunig) October 28, 2016

The Keyboard

The October 2016 MacBook Pro also featured “2nd-gen butterfly mechanism” keys for the first time. As some users have learned, these can be finicky and expensive to replace. “The New Macbook Keyboard Is Ruining My Life” writes Casey Johnston for the Outline: After the keyboard was apparently derailed by a literal piece of dust, Johnston learns or reminds us that “all of Apple’s keyboards are now composed of a single, irreparable piece of technology. There is no fixing it; there is only replacing half the computer.”

Not only is the keyboard finicky, but clearly the laptop isn’t designed to be repaired easily, if at all. This also precludes easy upgrading, not only by third parties but also by Apple.

Despite most of us not buying it for years, it’s worth noting that the last upgradeable Mac laptop went away today. https://t.co/RGQ1Mf00XQ https://t.co/lCPRi4qCCe

— Marco Arment (@marcoarment) October 27, 2016

Later Johnston relates a debatably even more cutting anecdote:

The Genius shrugged empathetically. He cast around and pointed to a nearby pre-2015 MacBook Pro with relatively thicker keys. “I have one of those,” he said apologetically. Though Apple employees receive significant yearly discounts on computers, and this was the first significant redesign of the MacBook Pro’s body in eight years, he had chosen not to buy one of the new ones, even a year later.

The RAM Limit

I’ve been a sucker for tons of RAM for a while now. When I bought my Air in 2012 I chose to max out the RAM to 8 GB. Right now, writing and listening to Spotify with Chrome, Firefox, and Wire running, Activity Monitor tells me I’m using 6.15 GB of RAM (though Neofetch reports “Memory: 2949MiB / 8192MiB”). Thus I’m glad I chose to bump up the default 4 GB.

But for a new laptop, one that I’d want to last till 2022 or 2023, I certainly wanted at least 16 GB of RAM, if not 32 GB. However, in 2017, you can’t buy a laptop from Apple with more than 16 GB. I don’t know what I’ll want to do with my computer in 2022, but knowing me it’s a good bet it’s gonna take more RAM than what I’m doing right now. As one example, running a virtual machine (or two!) costs RAM.

Other specs seem to have flatlined as well. Shortly after the Apple event, Quartz tech reporter Mike Murphy realized he’d likely be buying a new machine with a slower processor, reflecting the comment by the Apple Genius that Johnston related.

Ok this just convinced me: I’m not buying a computer that’s slower than my old one

— Mike Murphy (@mcwm) November 30, 2016

(even if it’s an apples and oranges comparison) pic.twitter.com/PfL9a3ktAw

MacOS Updates and the Apple Eco-System

Back in 2015 I read an interesting complaint about Mac’s tied-together ecosystem and pesky requests (or demands) for users to update software in a blog post by Bryan Horstmann-Allen (h/t Paul Ford):

Around OS X 10.9, though, things started going wrong. 10.10 improved a few of these things, but overall it just kept degrading. It’s slower, there are a lot of really distracting “features” I can’t seem to actually reliably disable: It’s tied into my phone, and my wife’s phone, so when she adds events I get duplicate notifications (deliver once being a fallacy, I suppose), disrupting me from my work. I disable this, but… It harasses me every day to upgrade. It desperately wants to just upgrade whenever it wants. More and more it acts like the Windows machines I’ve had to support over the last 20 years, which is deeply frustrating. It regularly does things in the background without asking, consuming all my bandwidth…

Two months after I read that post, Christine Teigen tweeted something similar:

Hate this macbook relationship. "When do you want to update?" "Later" "later today or later tomorrow?" Oh my god just fucking LATER

— christine teigen (@chrissyteigen) January 22, 2016

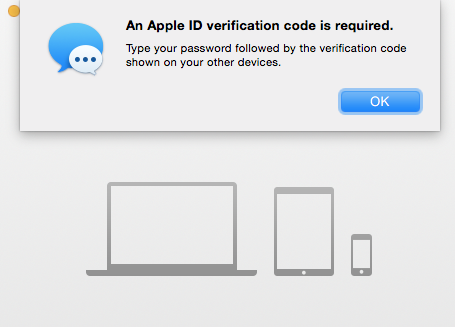

Besides the updates, I’ve had macOS seemingly randomly but frequently ask me for my AppleID password. This frequent ask is made even more annoying because I have two-factor authentication enabled on my Apple account. I’m still running 10.10 so this may have been improved by now, but, once I enter my text password, I get this cryptic pop-up:

My iPhone usually gets a verification code, but when I enter my text password with the code tacked on, half the time the prompt just reappears asking for my password again. In addition to this being annoying, it’s also debatably a security risk, as Apple is training users to enter their Apple ID credentials into a pop-up dialog that appears at seemingly random times. Again, this totally could be an issue with 10.10 that’s been smoothed out in 10.11+, but still, a company like Apple should support older versions of their OS.

The iPad-ification of the MacBook

Touch Bar

The addition of a Touch Bar seems like an iPad-ification of my precious platonic ideal of a laptop. Would a DJ really use it? Would I use it when editing video or coding? I’ve gotten pretty efficient with my keyboard and mouse. Admittedly, having a Touch Bar wouldn’t have prevented me from doing anything I would want to do with a laptop, but if it signals what Apple thinks its customers want, I’m not too jazzed about the direction.

Owen Williams titled his post about the event “Apple just told the world it has no idea who the Mac is for”:

It took four years to add a touch bar to the keyboard, which delayed any meaningful progress in the meantime? Apple’s customers are those that need powerful machines, but it delayed them infinitely for what amounts to a vanity project that the core demographic of Apple’s customers probably won’t even use.

Currently you can get a new Pro without the Touch Bar, but then you only get two Thunderbolt ports, one of which would be used for charging.

MacOS De-prioritization

For me, one of the sharpest arguments against the new MacBooks comes from this Bloomberg story by Mark Gurman two months after the event, which is headlined “How Apple Alienated Mac Loyalists”.

Interviews with people familiar with Apple’s inner workings reveal that the Mac is getting far less attention than it once did. They say the Mac team has lost clout with the famed industrial design group led by Jony Ive and the company’s software team. They also describe a lack of clear direction from senior management, departures of key people working on Mac hardware and technical challenges that have delayed the roll-out of new computers.

and later:

In another sign that the company has prioritized the iPhone, Apple re-organized its software engineering department so there’s no longer a dedicated Mac operating system team. There is now just one team, and most of the engineers are iOS first, giving the people working on the iPhone and iPad more power.

Since then nothing has rekindled any excitement about Apple’s operating system for me. I haven’t seen much to write home about in the last couple of macOS versions. As Ars Technica begins their review of High Sierra (fall 2017): “If you’ve felt like the last few macOS releases have been a little light, High Sierra won’t change your mind.” Steady is good, of course, but to me, in addition to the Bloomberg report that there will no longer by a dedicated macOS team, it was more evidence that there likely isn’t much new and shiny coming down the macOS pipeline.

Then, of course, on November 28th, 2017, we learned that macOS High Sierra had a significant security bug that allows anyone to get admin privileges without a password. Of course all software has bugs, but this one seemed particularly egregious from a company that stresses security and sells on a certain polished-ness.

A month later we learned that Apple plans to let developers write one app for iPhone, iPad, and Mac, which is pretty cool! But it just shows that the ecosystems will be merging even further in the near future.

As if to sum this up, Tim Cook, while speaking about the iPad Pro in January 2016, said, “I think if you’re looking at a PC, why would you buy a PC anymore? No really, why would you buy one?” (h/t Owen Williams)

No one asks to be buried with his iPad

Allow me yet another detour. In 2015 Tim Wu titled a New Yorker blog post “No One Asks To Be Buried With His iPad”. Wu explores this phrase, which has stuck with me, more directly in another post called “The Problem with Easy Technology”, which even features a Steve Jobs reference:

Just how demanding do we want our technologies to be? It is a question faced by the designers of nearly every tool, from tablet computers to kitchen appliances. A dominant if often unexamined logic favors making everything as easy as possible. Innovators like Alan Kay and Steve Jobs are celebrated for making previously daunting technologies usable by anyone.

It’s easy to see this in the video of the October 2016 Apple event. You can plug the power cord into any of the four Thunderbolt ports! Slide your finger on this pretty screen and your photos get better! It just works! And if, for some weird reason, it doesn’t, well there’s always a Genius Bar nearby.

Wu gets much more philosophical in the post, even suggesting that “demanding technology” is important for human evolution. First, let’s see his definition of the term: It’s “technology that takes time to master, whose usage is highly occupying, and whose operation includes some real risk of failure.” And while he stresses that “there is much to be said for the convenience technologies,” there’s something necessary, biologically, to demanding technology:

The choice between demanding and easy technologies may be crucial to what we have called technological evolution. We are, as I argued in my most recent piece in this series, self-evolving. We make ourselves into what we, as a species, will become, mainly through our choices as consumers. If you accept these premises, our choice of technological tools becomes all-important; by the logic of biological atrophy, our unused skills and capacities tend to melt away, like the tail of an ape. It may sound overly dramatic, but the use of demanding technologies may actually be important to the future of the human race…

Anecdotally, when people describe what matters to them, second only to human relationships is usually the mastery of some demanding tool. Playing the guitar, fishing, golfing, rock-climbing, sculpting, and painting all demand mastery of stubborn tools that often fail to do what we want. Perhaps the key to these and other demanding technologies is that they constantly require new learning. The brain is stimulated and forced to change. Conversely, when things are too easy, as a species we may become like unchallenged schoolchildren, sullen and perpetually dissatisfied.

In Mary H.K. Choi’s 2016 piece “LIKE. FLIRT. GHOST: A JOURNEY INTO THE SOCIAL MEDIA LIVES OF TEENS” in Wired a 15-year-old named Ubakim puts it a little more vaguely but in fewer words: “Ubakum loves her phone. Deeply. iPhones for her are too easy, a little basic. ‘I’m not a fan of user-friendliness.’”

MacBook Alternatives

If not a Macbook, then what? I slowly began to do some research.

I started a list of requirements: For hardware, I wrote that I wanted at least 16 GB of RAM, 3 USB ports, 13” screen at least, and decent battery life. But what about operating system and software?

First off, let’s get this out of the way early: I did not want to switch to Windows. One of my initial motivations to leave Apple was to use more free and open source software, which Microsoft is very far from. But on top of that, Windows 10 is apparently a bit of privacy nightmare and collects a lot of private information (see: “Even when told not to, Windows 10 just can’t stop talking to Microsoft” and “Windows 10 Reserves The Right To Block Pirated Games And ‘Unauthorized’ Hardware”), though there are apparently some steps you can take to protect yourself.

Another intriguing option would have been a Chromebook, but I wanted something with a big hard drive and the ability to easily run a variety of software, not just what I could find in the Android app store or coerce into running on Chrome OS.

Most of Coding Freedom is about the development of Linux, a free/open source operating system started in 1991. Could Linux do all the things I wanted to do?

So, What is Linux?

Coincidentally, the New York Times just this week published a very short “tech tips” about Linux as an alternative to Windows. J. D. Biersdorfer writes:

Linux, the open-source operating system project first developed by Linus Torvalds in 1991, is now used by millions of people on desktop computers, mobile devices and servers; Google’s Android and Chrome OS even have Linux roots. Because the software has been free and open for developers to enhance and improve for years, Linux is now available in many versions (typically called “distributions”) that vary in complexity and user interface.

In terms of being able to do everything a Windows desktop can do, a Linux system is certainly capable of most common tasks, like browsing the web, sending and receiving email, creating documents and spreadsheets, streaming music and editing photos. Many Linux distributions include all the basic programs you need, and you can install others from Linux software repositories online, but make a list of everything you need to do on the computer and make sure you have a Linux solution for it.

I’m not going to go in to a ton of specifics about what Linux is or even what it’s like to use it – in my limited experience it’s generally not significantly different from Windows or macOS from a user’s perspective (though up to even just a few years ago it sounds like it was much more difficult than its commercial counterparts). But I’ll try to explain one concept about that really pulled me toward it and away from Apple, besides the Rilke.

The Flexibility of Linux

I’ve already written about free software and some of its (at least theoretical) benefits. Not only is Linux and all the programs it comes with open source, but for the most part all of the software you’d ever install on a Linux machine will generally need to be open source– most closed-sourced software (Microsoft Office, Adobe Photoshop, etc.) can’t run on Linux. I was in fact excited to be forced to find free alternatives to proprietary software like Microsoft Excel and iTunes. But first, more about Linux.

As Biersdorfer writes, Linux comes in different versions, known as distributions (examples include Ubuntu, Mint, Fedora, Manjaro, Arch, etc.). Additionally, most of these distributions can use a variety of different desktop environments (e.g. Gnome, KDE, Xfce, etc.). A desktop environment is the part of the operating system that the user interacts with most – it includes the file manager, the menus like wifi, date and time, etc., some the default applications, notifications, all that stuff. Wikipedia defines it as:

A desktop environment (DE) is an implementation of the desktop metaphor made of a bundle of programs running on top of a computer operating system, which share a common graphical user interface (GUI), sometimes described as a graphical shell.

Here’s a nice video that shows five different desktop environments available to most Linux users:

That YouTuber, Joe Collins, has a slightly more involved and technical video called “The Linux Desktop Demystied” that helped me better understand some of the ins and outs. He’s also got another video on the Gnome 3 desktop environment specifically. (There are tons of great videos about Linux on Youtube, and I learned a lot from them.)

Surprisingly, it is not too difficult to install a completely new distribution or DE, and of course it costs nothing (you just have to be sure to back-up your files first in some cases). In fact it seems common enough that there’s a subreddit called DistroHopping where users discuss their frequent distribution (“distro”) changes and installations.

This flexibility – being able to choose not only the Linux distribution you want, but also what desktop environment – seems very powerful to me. For example, when I installed wanted to try installing Linux on my 2009 MacBook, I knew it was underpowered in terms of resources by modern standards, particularly in terms of RAM. After some research I opted for Ubuntu for a distribution and a desktop environment called Xfce, since I had learned that that combination did not require a lot of resources, including RAM. It’s not blazing fast, but it runs pretty well!

By contrast, there are of course no distributions of MacOS, and Apple only offers one desktop environment (which I believe is called Aqua). I’m almost positive that my 2009 MacBook Pro would barely be able to run macOS High Sierra.

This flexibility also offers a certain amount of protection against any design changes that a given distribution’s or DE’s developers choose to implement – if a user disagrees with a sharp change, he or she can just install a new distro or DE easily and at no cost. Apple doesn’t make a ton of changes to macOS these days, but if they did, regular Mac users wouldn’t have much recourse. By contrast, some Linux distributions like Arch push significant changes on a rolling schedule, since they’re confident their users want to be on a bleeding edge, while others, like Debian, move very slowly and cautiously.

But Can Linux Do Everything I Need it to Do?

At some point early on in my search I wrote out a quick list of things I primarily used my Macbook Air for, as Biersdorfer advises:

- Internet browsing (Chrome? Chrome extensions? TweetDeck?)

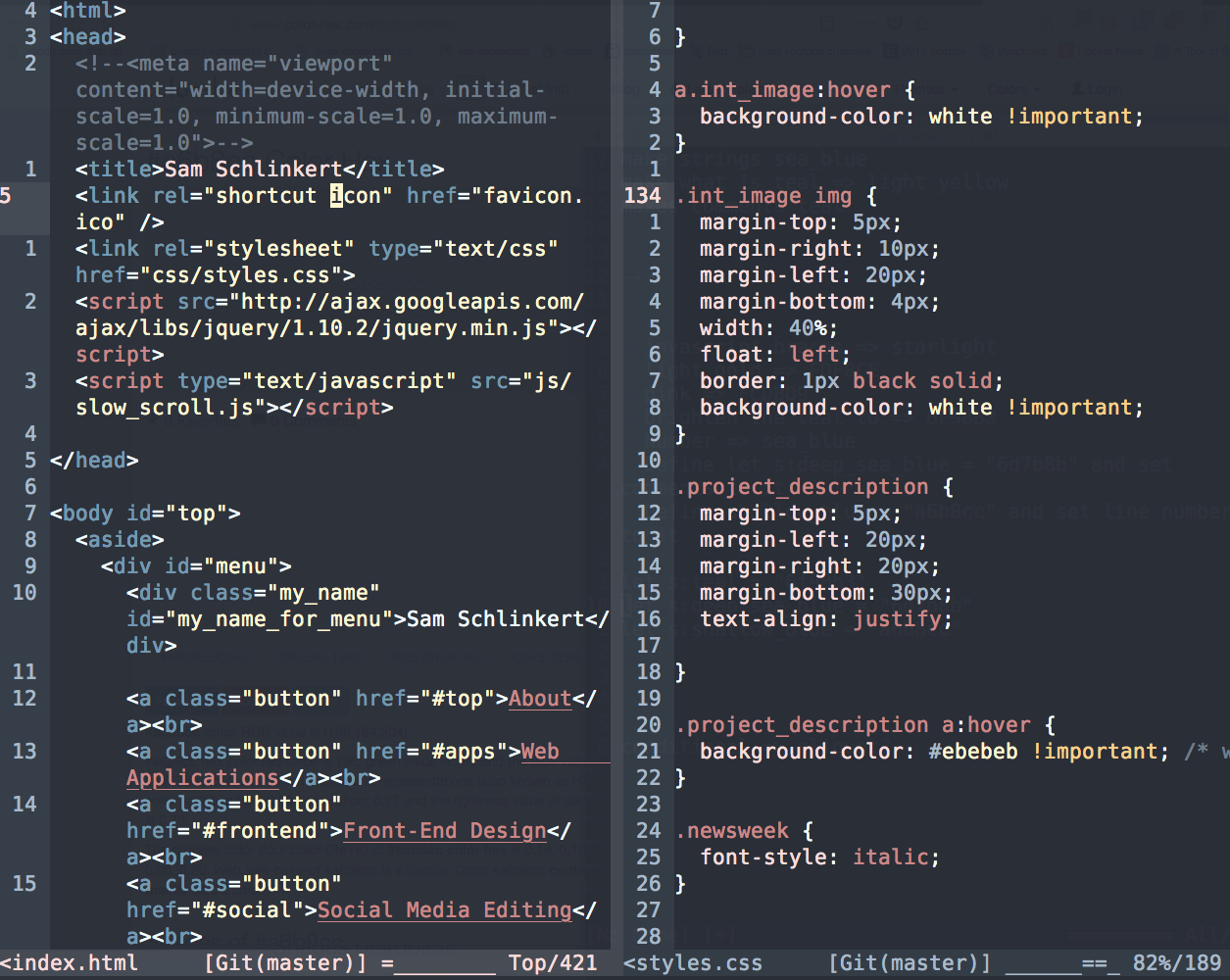

- Writing and running code (Vim, Ruby, etc.)

- Instant Messaging (gchat, etc.)

- Playing MP3s

- Spotify

- Netflix, Hulu, HBO Go, etc.

- Password management (1Password?)

- Use GPG through a GUI application

Could I do all of these things on a computer running Linux? To find out, I needed a computer with Linux on it to play with. Cue research montage: I started reading a bunch of subreddits every day, including r/linux, r/linux4noobs, r/LinuxOnLaptops, r/Ubuntu, and r/linuxhardware. By November 7th, after a couple of false starts I successfully got Ubuntu installed on an old MacBook Pro. Ubuntu, I had learned, was one of the “starter” Linux distributions.

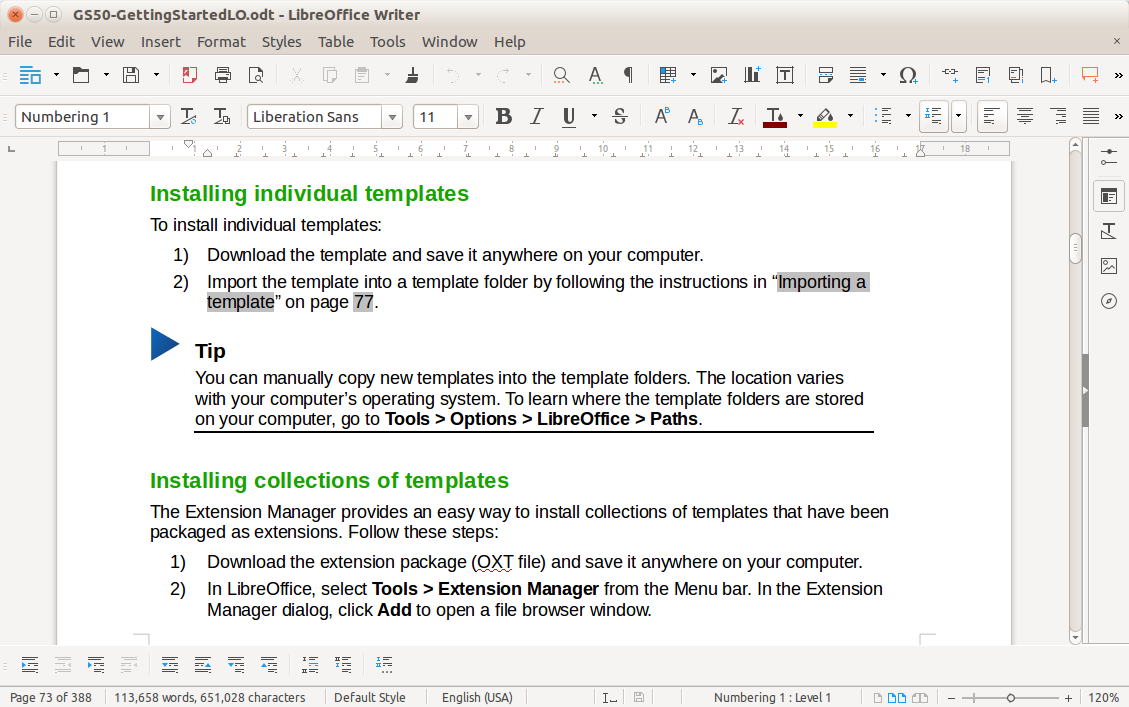

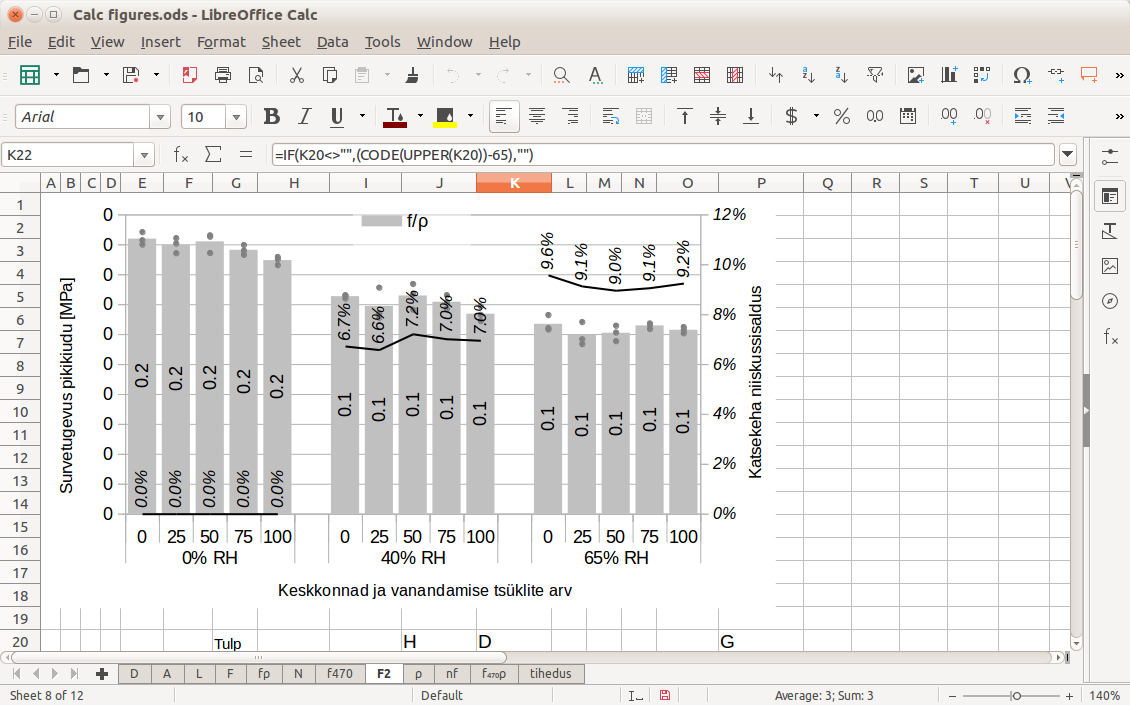

One of the first things I did on Ubuntu was to create a spreadsheet using LibreOffice– a suite of free software that emulates Microsoft Office and is included with Ubuntu 16.04. I called the first column “Task name” and a second labeled “Result” and slowly went down the list.

The tl;dr here is that, as Biersdorfer writes, Linux can handle most of my common tasks. I really only have two major hang ups at this point: I can’t run iMessage, and while Hulu works in Chrome, I still haven’t gotten HBO Go to work. I worked around these problems: Most people I text with have moved away from iMessage, and since I pay for HBO through my Hulu account, I can watch HBO content through Hulu’s new-ish beta site, which works on Linux in Chrome.

What It’s Like to Install Software on Linux

How you install software on Linux depends quite a bit on which distro you’re running. For a popular distribution called Ubuntu, there are a number of ways. The simplest is to use the built-in application store, which is very similar to Apple’s. Other times the recommended installation process is to download an installer, often with the .deb extension, similar to .dmg files for MacOS.

But often times a piece of software requires users to run a command or two from the command line (there’s a general assumption that if you’re running Linux, you at least know how to open a terminal and run a command). For example, installing the Signal desktop client on Mac follows the familiar flow of downloading an installer file. By contrast, for Debian-based Linux (Ubuntu is Debian based), users need to run these three commands in the terminal:

curl -s https://updates.signal.org/desktop/apt/keys.asc | sudo apt-key add -

echo "deb [arch=amd64] https://updates.signal.org/desktop/apt xenial main" | sudo tee -a /etc/apt/sources.list.d/signal-xenial.list

sudo apt update && sudo apt install signal-desktop

Once you run those three commands Signal is installed. You don’t need to write any code, but you do have to often paste commands like these into the terminal to install software on Linux. But I consider this one of Wu’s technological demands.

Finding a Modern Computer to Buy to Run Linux

Over the next few months I filled out a different spreadsheet with a number of laptops that either came with Linux on them or that I could easily install Linux on. I found that some companies sell computers with Linux already installed. With these computers, not only could I expect everything to work better out of the box, but I’d likely benefit from some support from the company, which, as a Linux newbie, I figured couldn’t hurt.

By now my loose hardware criteria was 16 GB or more of RAM, 512 GB of flash storage, 13” to 15” screen, plenty of ports, all for somewhere around $1,800. I also wanted the laptop to be able to run two external monitors if I wanted – this proved to be one of the hardest requirements to fulfill.

I soon found that Dell sells some of its laptops with an option to have Ubuntu installed on it rather than Windows, including one its newer and more sleek models, the XPS 13 (“The XPS 13 DE: Dell continues to build a reliable Linux lineage,” Ars Technica wrote at the time). This is thanks to a team at Dell known as “Project Sputnik” that pre-installs Ubuntu on Dell computers, making sure they run it smoothly. The team recently celebrated its 5th anniversary, so clearly they’re doing something to please the Dell executives. (You can watch a 2017 interview with the team’s leader Barton George.)

In addition to the XPS 13, Dell also currently offers Ubuntu on their New Precision 3520, New Precision 5520 and New Precision 7520, among others. It was weirdly difficult for me to find a clean list of all of their Ubuntu offerings, and in general their website is ugly and hard to use, though I think they do have a landing page for “Ubuntu-based Developer and Engineering systems”.

I also found about a company called System76 based in Colorado that basically buys laptop shells from China and other parts, assembles it all, and puts either Ubuntu or their new distribution, which has the ridiculously-stylized name of Pop!_OS, on it for you. The models I considered were the Lemur, Oryx Pro, and their new Galago Pro.

I had read on Reddit that ThinkPads – both old/used and new – were good candidates for installing Linux on yourself. Among the new options, the T470 and T470s looked particularly strong (the T470s is Wirecutter’s pick for best business laptop), as well as the P50s. For something sleeker, the X1 Carbon looks nice – Wirecutter named it their upgrade pick. If money were no object I’d consider getting an X1 just for travel.

I also put MacBook Pro and Air options into the spreadsheet for comparison.

Finalists

After listing more than 30 model and configuration options, I narrowed my list down to four options.

System76 Galago Pro: 32 GB of RAM, 1 TB flash storage + 1 TB HDD, 3.4 GHz max processor speed (i5-8250U). Approximately $1,800.

System76 Oryx Pro: 32 GB of RAM, 512 GB flash storage + 1 TB HDD, 3.8 GHz max processor speed (i7-7700HQ). About $2,200.

ThinkPad T470: 32 GB of RAM, 1 TB flash storage, 3.5 GHz max processor speed (i7-7500U). $2,039.

Dell New Precision 5520: 32 GB of RAM, M.2 PCIe 512GB SSD Class 40 + additional 2TB 2.5 inch 5400rpm HDD; 15.6” UltraSharp FHD IPS (1920x1080), Non-touch; ports: 2 USB 3.0, Thunderbolt 3, and an HDMI. $2,016.60.

And for comparison: MacBook Pro: Touch Bar, 13” screen, 16 GB of RAM, 512 GB flash storage, 3.5 GHz max processor speed (7th Gen i5). $2,199.

Let’s start with the Dell.

I think I wrote off the Dells early partially because I owned and used their desktops, running Windows, as a kid and so the idea of returning to that hardware felt boring. That said, I think that 5520 is a pretty safe, not exotic choice. I could likely connect two external monitors to it using the HDMI and the Thunderbolt ports, and even if that didn’t work I think I could use something like the Dell Business Thunderbolt Dock - TB16 to get a bunch more ports for an extra $350. Since I made my choice (no spoilers!), Dell has released an updated XPS 13 that looks pretty great.

I didn’t put much effort into looking into the ThinkPad options either. The idea of wiping Windows and installing Linux myself, with no official support at all, daunted me. I’ll also note that I was shocked by hard it was to navigate the Dell and ThinkPad websites.

The Galago Pro is System76’s newest laptop. It’s about the size of my trusty MacBook Air, with a few more ports and a HiDPI screen standard (which is kind of like Apple’s Retina screens).

Overall it seems like a pretty great laptop, and a good choice for anyone who has read this far. However I saw a review on YouTube that found a few dealbreakers. This reviewer thought that the graphics card and other hardware included in the Galago Pro weren’t quite powerful enough for the 3200 px by 1800 px HiDPI screen. There’s also an issue of how well Linux handles HiDPI screens, especially when plugging in external monitors that are not HiDPI (though System76 have worked on this issue with their own distribution, Pop!_OS). Lastly, some older applications don’t work well with HiDPI screens.

As I understand it, one workaround is that you can just run the screen at lower resolution, like 1920 by 1080 pixels, and avoid almost all of these issues. But I was worried the company had made other sacrifices for portability that might not be obvious to me right way. For example, battery life on the Galago Pro, according to a few reviewers, is only about four hours. And that same YouTube review shows how flimsy the top half of the laptop is.

Overall I think the Galago Pro is a pretty solid choice for most people. I’m curious what they change in the next version. But for me, especially after I looked at the Oryx Pro, I wanted something with more power, and I was willing to sacrifice a lot of portability for it.

The Oryx Pro

The Oryx Pro is the computer I finally bought in November 2017, almost a year after making my original spreadsheets.

I got the model with a 15.6” screen and configured it with an i7-7700HQ processor (2.8 GHz up to 3.8 GHz), 32 GB of DDR4 RAM, a 512 GB NVMe solid state hard drive with an additional 1 TB hard drive, and a Nvidia GTX 1060 graphics card (6 GB). It’s given weight is 5.5 lbs and its dimensions are 15.2″ × 10.7″ × 0.9″ (38.51 × 27.10 × 2.49 cm). It’s also got a ton of ports, including 2 MiniDisplay ports, 3 USB-A ports, 2 USB-C ports, an Ethernet port, and more. It’s not super pretty (here’s a video that gives you a good look at it), but it is, by almost any measure, a beast of a laptop.

System76 currently offers a choice of two distros: Ubuntu 16.04 or their own distro, called Pop!_OS, which is of course free and on GitHub. But given how similar different versions of Linux are, I figured I could put any distribution on it that I wanted on it. Thus I was mostly looking at it from a hardware prospective. I can now agree with most reviews I read: it feels pretty sturdy. The trackpad is fine– I appreciate the dedicated buttons – and while the keyboard isn’t as “snappy” as on my Air, I actually like it. Though I knew I would be mostly using my mechanical keyboard and a Logitech mouse.

Given the choice of those two distros, I opted for System76’s new, homegrown distribution, Pop!_OS, which comes with a desktop environment called Gnome. This combination, thanks in part to efforts of System76’s engineers, work well together out of the box. I paid about $2,200, with some savings from their holiday sale.

A Note on System76

Let me just note here that one of the less tangible things I bought with my Oryx Pro was support from System76. While I only got the minimum 1 year warranty for “limits parts and labor,” the company says they offer a lifetime of Linux support. This was heartening, since in abandoning Apple I was also losing all those Genius Bars! And while I had witnessed how helpful the online Linux community was, I wanted something a little more than that if I was going to dump more than $2,000 into a machine – far more than I’ve spent on any one Apple product.

Also, from my perspective the people at System76 seem almost comically awesome. One of their engineers answered a number of questions I threw at him on Mastodon. Another is building an operating system written in Rust as a side project. I haven’t asked a question any questions through the official System76 support portal, but I have no reason to think they wouldn’t handle it quickly and thoroughly.

After I had an ordered my Oryx Pro, a security issue involving something called Intel’s Management Engine was made public. System76 promptly announced that it was disabling it in all of its laptops, including the ones it sold in the past few years, through a firmware update, something that Dell is only doing on some very expensive models. To explain their reasoning, System76’s CEO and one of their engineers did an interview with Bryan Lunduke about it (Note: System76 is a sponsor of Lunduke’s YouTube show, which he discloses in the interview), plus another engineer held an impromptu AMA on a Reddit post about the Intel ME issue.

Lastly, reflecting their commitment to some of the ethos Coleman discusses, I love how the fourth link down on their Pop!_OS documentation page is titled “Getting Started with Bitesize Bugs”, which outlines the process of fixing small bugs in their operating system. It’s almost impossible to imagine Apple having something like that.

OK so I like the company, but what kind of free software would I have to be using with Linux?

What Software I’m Using on Linux

Overall I haven’t had to sacrifice much. (System76 wisely has an article on switching from Apple.) The category where Linux and free software is furthest behind seems to be in photo and video editing – think about Adobe’s monopoly on that sector.

LibreOffice instead of Microsoft Office: Seems fine. Again, I rarely used Office on my Mac. I suppose if I have to make a spreadsheet and chart at home I’ll have to Google “Libre Office calc [my problem]” rather than “Excel [my problem]” to get help, but I’ll take my chances. I also of course can still use Google Docs and Google Sheets.

For code editing I’m using Neovim, which I used on macOS as well. (Sublime and Atom both offer Linux apps if you prefer those editors.) As you might have guessed, Linux is very similar to Mac from the command line: rbenv for Ruby and Rustup work just as they do on macOS.

For my browser, Firefox

Firefox seems to be the default on most Linux distributions, including Pop!_OS. Firefox, luckily, just released a much-improved version, 57. However I ended up installing Chrome to get Hulu to work, which I feel bad about because Chrome is not free software, but it’s an example of one case where Linux can run non-free software.

For password manager I switched almost completely to KeePassXC. I had been using 1Password, but they don’t have a native app for Linux. Though recently 1Password released 1Password X, a browser extension solution for password management that apparently works on all operating systems. I don’t see why the LastPass browser extension wouldn’t work on Linux.

For chat/IM, I’m pretty sure I can run gchat in Chrome through gmail’s web interface if I need to. However over the course of the last year I’ve moved most of my friends to other messaging services like Wire or Signal, both of which offer Linux apps. One bummer here, as mentioned, is that I can’t run iMessage, but I can obviously still send iMessages from my iPhone.

For cloud-synced notes I use Standard Notes, which has a Linux app. DropBox works on Linux too if that’s your bag.

For updating my personal website I can keep my FTP client, Filezilla, a free application that I had been using on my Mac. For making GIFs I was sad to give up GIF Brewery and GIPHY Capture, but I’ve been playing with Peek. VLC works just fine on Linux for playing videos. If I used an email client, I’d likely install Thunderbird, but so far I’ve been using GMail’s web interface in Chrome, which works normally.

For more on what I did when I initially booted up Pop!_OS, here’s a Github repo where I took notes.

Software I’ll Eventually Install

- For RAW photo editing I’ll have to give up Adobe Lightroom for something like Dark Table. I haven’t installed Dark Table yet though– that’ll be a project for another day.

- For editing video, which I generally only do at work, there’s Kdenlive and Openshot

- Spotify runs on Linux, which is super cool. But for playing MP3s, there are a lot of options here. Two I’ve heard good things about are Clementine and Lollypop. Honestly I’m pretty confident I can find something better than iTunes, which doesn’t seem to be much of a focus for Apple in recent years.

Should I Switch to Linux?

First off, I have glossed over a lot of little tricky things I had to either know or do to feel comfortable using Linux. I’m really glad I took a year to learn about little things, like the difference between X Org and Wayland, the pros and cons of using Nvidia drivers, what a PPA is and how they’re different from snaps, etc.. And I’m also glad that I was already comfortable using a terminal (as we saw, even installing software sometimes requires using the command line. While many distros, including Pop!_OS, have GUI software stores similar to Apple’s App Store (except that EVERYTHING IS FREE), I’m not sure I can recommend Linux to users who have never touched a command line.)

In general I’m glad I was able to deal with a little messiness, to not be too pissed when something breaks and I need to Google an error message with the faith that someone has had it before and recorded how they fixed it, so I can solve it without an appointment at the Apple Genius Bar and maybe learn something about computers in the process.

It’s pretty great to be at least a little more free, blooming a few more colors.