A few years ago I got interested in passphrases (as passwords) and the word lists used to generate them. Even the methods of creating these passwords, notably using dice, fascinates me.

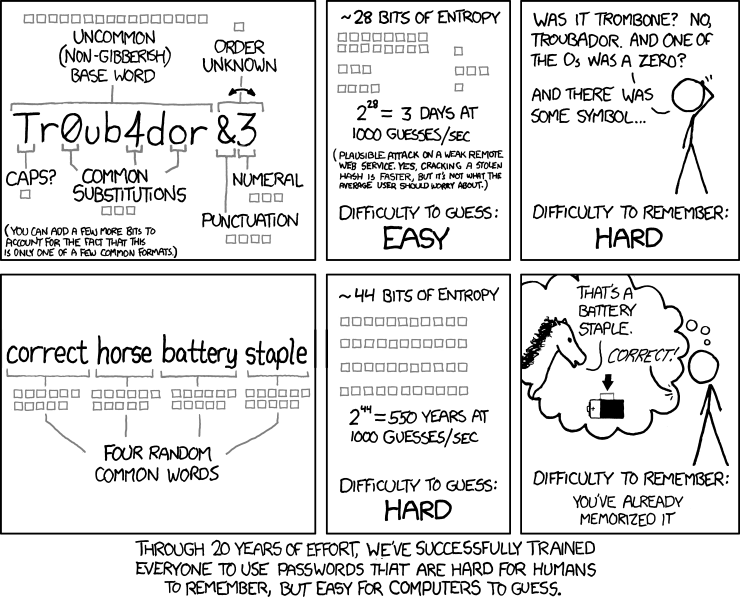

Turns out a string of randomly chosen words can be difficult for a computer to guess, but still easy for a person to remember, especially if we use a bit of story-telling.

To me, in an age where computers are doing more and more things that people thought they could never do (for example dominate the game of go) this seemed to be a neat example of humans, even young ones, still being able to coolly triumph over machine in an arena where it might seem like computers would have an advantage. As a journalist, I particularly enjoy that this is thanks in part to humankind’s ability to construct and recall narratives. It feels particularly human, and maybe Didionesque.

Where do these words come from?

There are a few popular word lists in use today, the king of the bunch seemingly the EFF long list, which contains 7,776 words.

1Password has their own word list for when users randomly generate password. 1Password’s list is 18,328 words long, so each word adds more “randomness” or strength (commonly measured in bits of entropy) to a generated password as compared to the EFF long list. (To be specific, each word from the 1Password list adds about 14.16 bits of entropy, while a word from the EFF long list adds 12.92 bits.) Of course the downside is that, since it has more words, presumably some of the words are more esoteric and potentially harder for more people to remember or pronounce. Some examples: “aggeus”, “bildad”, “englex”, “faubourg”, and “mytholog” – not exactly correct horse battery stapler.

The question of prefix words

Length isn’t the only choice that these word list makers face. If a list contains “prefix words” (also known as “prefix codes”), users should not be permitted to create passphrases in which no punctuation separates words (e.g. “denimawningbondedreturncamisolepebblecrewlessbook”).

I learned about this issue while watching this YouTube video called “Diceware & Passwords”, which offers a nice introduction to a method of generating these random passphrases using dice. About 8 minutes in the presenter, Dr. Mike Pound, explains something that perked my ears up: He explained that you need spaces (or other punctuation) in between the words because “sometimes you might accidentally join two words together and they’d actually be a different word on their and in which case your [phrase] goes down to four words.”

Here’s the hypothetical he’s describing: What if we just mashed our words together, so instead of “casket-stoppage-desk-top” we just used “casketstoppagedesktop” as our password. The problem here is that, if “desktop” is also a word on your word list (and thus on a hypothetical and informed attacker’s list), this passphrase is only a three-word phrase, which is notably weaker than a four-word phrase. The user thinks they have the security of a four-word phrase, when they really only have three. Note that this would only happen in rare cases when two words that make a compound word that’s on list are right next to each other, and, of course, the user chooses not put anything between the words. It’s important to note that if there is punctuation or a space between the words, this problem does not exist. Using TitleCase is another solution.

You can read more about this issue here.

Returning to the example lists I mentioned above, the EFF long list does not have prefix words, but the 1Password list does. This means that the EFF list can be used to make passwords without punctuation between the words, but the 1Password list should not. As it turns out, 1Password’s password generator forces users to choose punctuation to be placed between the words, and thus the strength (or entropy) of the created passphrases is not affected.

How might I go about creating a word list?

In early August of this year I saw this post on 1Password’s community forum, in which a user complained about some of the more strange words on their list and the problems they can cause:

Memorable Words are a great way to communicate between humans, but if one of the words generated is actually misspelt, it will cause confusion and failure.

I generated a password that included the word ‘wierd’, and copy/pasted it into use. I typed it into my phone to send out-of-band to a supplier … where it got autocorrected, and I didn’t notice, and of course they couldn’t use the word they received successfully.

For their part, a 1Password employee did respond, saying they would bring the issue up with their security team. I haven’t seen any updates since, though I may have missed them. Regardless, the thought that a company that makes a very popular password manager didn’t have a good word list made me wonder how I might go about improving their list, or even making my own.

Commonly used words from Google Books Ngrams

At some point I decided to start from scratch. I figured I wanted a list about as long as 1Password’s, but if possible, have it be free of prefix words. For the words themselves, I wanted them to be the most commonly used, since users would need to weave them into little narratives like correct horses, or at least remember them for a few seconds as they typed them into a mobile device.

To get a list of common words, I explored Google Books Ngram public data, which you may be familiar with due to their entertaining Viewer web product.

Satisfied that this data was available and looked useful to me, I started building a scraper and parsing tool using BASH and Rust. I figured the “1-grams” (single words) data compiled in 2012 would do fine. That data is broken up into separate word lists, based on starting letter of the word. For example, here’s the file f. Each file is a compressed tab-separated text file, with a line for each word-year. The f file alone has more than 47 million lines. For example, here’s a sample on the word “finches”:

finches_NOUN 1584 2 1

finches_NOUN 1603 1 1

finches_NOUN 1682 1 1

finches_NOUN 1688 1 1

finches_NOUN 1703 1 1

finches_NOUN 1716 1 1

finches_NOUN 1725 1 1

finches_NOUN 1729 1 1

finches_NOUN 1730 2 2

finches_NOUN 1733 1 1

...

finches_NOUN 2005 5382 1799

finches_NOUN 2006 5973 1992

finches_NOUN 2007 6236 2119

finches_NOUN 2008 7593 2730

The first number is the year, the second number is overall occurrences in Google Books, and the third number is how many “distinct” books it appeared in that year. In some instances it even listed the part of speech. Pretty cool!

Cleaning the data to create a “raw” word list

While there’s tons of interesting information in these files, I didn’t need a lot of it. For example, I wanted to give words like “finches” – regardless of its part of speech or various capitalizations – a single, quantitative “score” to represent its “commonness”.

First, I arbitrarily decided to discard any data from before 1975 (though it would be fun to a make 1920s list?). Then for any and all years after 1975 I added up the total number of appearances of the word (second number) into one numerical score. I also collapsed capitalizations and parts of speech into one “word”.

This procedure gave “finches” a score of 291,922, placing it just below “florins” (292,262) and “foibles” (291,693).

I went through each letter of the alphabet, calculating a score for each word and then appending the top 100,000 words starting with the letter into a CSV file, which weighed in at 2.2 millions lines. I then took the top 100,001 words from that CSV file to create a “raw” word list. Crucially, I left this list sorted by the appearance score (even though the score itself is not in the file). You can view that file here, though note that has many profane and offensive words.

A note on the code: BASH?

Again here’s a link to my Github repo for this project, gracefully named common_word_list_maker.

I used BASH to download and uncompress the files from Google. Thus, the code itself is not kicked off by the user running the familiar Rust command of cargo run, but rather executing a script I creatively called run.sh. No, I don’t love this aspect of this project; yes, I’d prefer if it was all in Rust. But I also wanted this project to be more about the end product than another Rust-learning expedition.

Cleaning the raw word list

As you might imagine, this 100k-word-long list wouldn’t make a good word list for generating passphrases. To begin with, the lowest-scoring words on this list are pretty strange: “todor”, “rew”, “biddulph”. Plus, given the way entropy is calculated, the benefits of a huge list like this has diminishing returns for per-word entropy: each word adds 16.61 bits of entropy. Compare that to a 33,000 word list, which adds roughly 15 bits and allows you to remove the 77,000 worst (however you want to define that) words. (Note: I’m a little confused about how important each additional bit is in terms of practical password strength.)

As a simple cleaning example, we could just take the top X number of words. Since the raw list is sorted by score, this means we’d get the most common X words. On *nix systems, we can use the head command: for example, to write the top 33,000 words to a new file, you could run head -33000 word_list_raw.txt > cleaned_word_list.txt.

Tidying up further

To cut down the list further and with a bit more nuance, I built a separate tool called Tidy, a command line tool specifically for combining and cleaning word lists. (It’s all Rust and is a bit more polished than my word-list making code.) Some options that are interesting to our problem include removing words below a minimum character count and removing prefix words.

We can also remove a list of rejected words, like words that are a little too common, or profane words (lists of which are a search query away). Tidy can also take a list of approved words and reject all others, like your Mac/Linux word dictionary, which, I learned from that 1Password forum thread, is located at /usr/share/dict/words and contains 102,305 words!

So as an example, you could run something like this:

tidy -o cleaned_word_list.txt -lPe -m 4 -a /usr/share/dict/words -r reject_words.txt word_list_raw.txt

An example of a usable word list (an end-product)

Using head and Tidy, I created an example word list, containing 16,607 words (and no prefix words). Attributes of the word list include:

- Each word from this list provides an additional 14.02 bits of entropy, close to a nice round number.

- Thus, a 7-word passphrase provides 98.14 bits of entropy. This is pretty close to 100 bits, which is what KeePassXC labels “excellent”.

- Since prefix words have been removed, passphrases created from this list aren’t required to have punctuation between the words to maintain its level of entropy. (Example: We’d be safe to use

spillsunmoveddissectionfadingminedtaperedeven though the first two words, “spills unmoved” could be 3 words – “spill sun moved” – because “spill” is a prefix word of “spills” and thus has been removed the list, preventing a user from ever generating the passphrasespill sun moved dissection fading mined tapered. Shout out to Reddit user BlueCyber007 for asking this question.)

Note that I haven’t manually scrolled through this example list, so there may be some offensive words remaining. (You can use Tidy’s reject words options to remove words.)

Currently, I am not actually using this example word list, or any product of this project, for creating passphrases or anything else. But it was a fun project!

Update from 2022: I’ve created more word lists using this method and others, including a proposed new list for 1Password.

Further questions to explore

Would a raw list that used the number of distinct word appearances from the Google Books Ngram data be better for our purposes?

A bigger question: What if we looked at the Google 2-gram data – words that frequently appear together. According to my casual calculations, things get nutty quickly. For example, if we had a list of the most common 1 billion 2-grams, each pair of words would add 29.9 bits of entropy, meaning three of them (6 words) would make a decent passphrase (~90 bits). Why might we want to construct a passphrase like this? Three 2-grams would likely be easier to remember than six 1-grams.

Galaxy brain: A list of 1,000,000,000,000,000 3-grams would give 49.8 bits per 3-gram (according to my math). Thus, two 3-grams would give almost 100 bits.

Tender wrap-up

I’m aware of the irony of starting a post about this project with phrases like “particularly human” and ending up explaining how I blindly scraped Google data to create this list, doing almost no manual editing of the list myself. But I think you could do worse when you consider that the underlying data, a sample of books – our stories! –, is pretty human.