In his last column of 2018, New York Times tech writer Farhad Manjoo offered some advice on “how to survive the next era of tech”: “Slow down and be mindful.”

While five years ago, Manjoo writes, “technology felt thrilling and world-changing,” it also felt confusing. Back then, “it was easy to get lost in the hype. It was also easy to pick the wrong horse.” Now, however, Manjoo observes that tech, in general, works better, but also that “the tech industry in 2018 is far more consequential than it was in 2014.”

Manjoo then offers three maxims for “an ethical and upstanding user of tech, navigate this misbegotten industry”: “Don’t just look at the product. Look at the business model,” “Avoid feeding the giants,” and “Adopt late. Slow down.”

As “the giants” (“Apple, Google, Facebook, Amazon and Microsoft”) get more powerful, I think those are all worthy resolutions for users of technology to carry into 2019.

But one thing that stuck out for me about a column that primarily addresses tech business models is that there’s no mention of free or open source software, software licensing, or Linux. I think this is more a failure of the free software movement to make in-roads in what I’ll call “mainstream tech,” but nevertheless the omission made me a bit sad for both parties.

Free software

In this context, “free” software doesn’t just mean software that you can get for $0 (“free as in beer”). Free software, or libre software, according to Wikipedia, is:

… computer software distributed under terms that allow users to run the software for any purpose as well as to study, change, and distribute it and any adapted versions. Free software is a matter of liberty, not price: user’s individually or in cooperation with computer programmers are free to do what they want with their copies of a free software… regardless of how much is paid to obtain the program. Computer programs are deemed free insofar as they give users (not just the developer) ultimate control over the first, thereby allowing them to control what their devices are programmed to do.

The source code of any given piece of free software is public – anyone can not only read it, but is free to run it and, if they choose, modify it. Developers donate their time and skills – knowing full well they will not be compensated monetarily outside of the relatively rare donation – to launch, develop, and make contributions to these software projects, improving them over time. If a significant amount of users do or don’t want a certain new change, they are free to create and maintain rival versions, or “forks,” of the software. The legal machinery for this system revolves around software licenses like the GPL license or the MIT license (check out Gabriella Coleman’s Coding Freedom for more).

What you (at least theoretically) end up with is software that effectively has no business model, or, if we must, runs on a gift economy. Only the larger projects (for example, operating systems) have formal monetary funding streams, which, as I understand it, are either run on donations from users or corporate sponsors, or run on profits from corporate customers. My chosen password manager, KeePassXC, has a webpage on how to donate, which includes a Patreon.

Crucially, these funding schemes seem to have very little in common with the traditional venture capital system most of us our used to from places like Silicon Valley, in which money will have to be made at some point, one way or the other, sometimes at the cost of the user’s privacy.

A personal challenge

About a year ago, with some of these ideas in mind, I set out on a personal challenge to use more free software. While I learned that I could switch from Google’s Chrome to Mozilla’s Firefox, from Microsoft Office to Libre Office, from Twitter to Mastodon even, I soon realized that to really jump into the world of free software, I’d have to ditch MacOS, a closed-source operating system owned by Apple, to an open operating system licensed as free software.

After a bit of research I decided Linux was at least worth a shot. I learned that, with Linux, I wouldn’t be able to use Adobe applications like Light Room and Photoshop (which is, understandably, a show-stopper for some people), nor could I use Microsoft Office programs, or run iMessage, iTunes (which, frankly, might be a pro for you), Airplay or most other Apple-made applications, not to mention access to the Apple Store and their Genius Bars (admittedly this could be a pro or a con, given your experience). And there are some hardware compatibilities to consider, for example Linux can struggle with “HiDPI” monitors, especially if used in tandem with standard DPI screens. Here’s a basic, slightly outdated overview on what it’s like to switch from Mac to one version of Linux called Ubuntu.

But once I confirmed that I could watch Netflix, load GMail’s site, listen to Spotify, write text, run code, open and edit a PowerPoint presentation in an application that’s not PowerPoint, and use my password manager, I figured I could get the hang of the rest as I went along. (Aside: Making a list of what you use your non-work computer to do is an interesting exercise! Especially considering how much you can do in a browser (i.e. Slack) and/or on a smartphone.)

(You can learn more about Linux from this brief New York Times Tech Tip!)

Buying into Linux

So, after a lot of more research which you can read about, in November of 2017 I ordered a laptop from a company based in Colorado called System76, which sells computers built for running Linux. System76 is not a “tech giant” by any means, in fact they actively contribute to and support free software that they of course know their users will use (to be fair, most large tech companies encourage their employees to create and contribute to open source software).

I’ve been using my Oryx Pro for about 15 months now, and overall I love it. I don’t think I’ll be going back to Apple for a computer any time soon. That said, to use it, I’ve had to do things that most users of computers I know would balk at, like opening the terminal. (I’ll note that I did have to ship my laptop back to System76 for a repair, but with my one-year warranty it was all free. And System76 offers a lifetime of software support.)

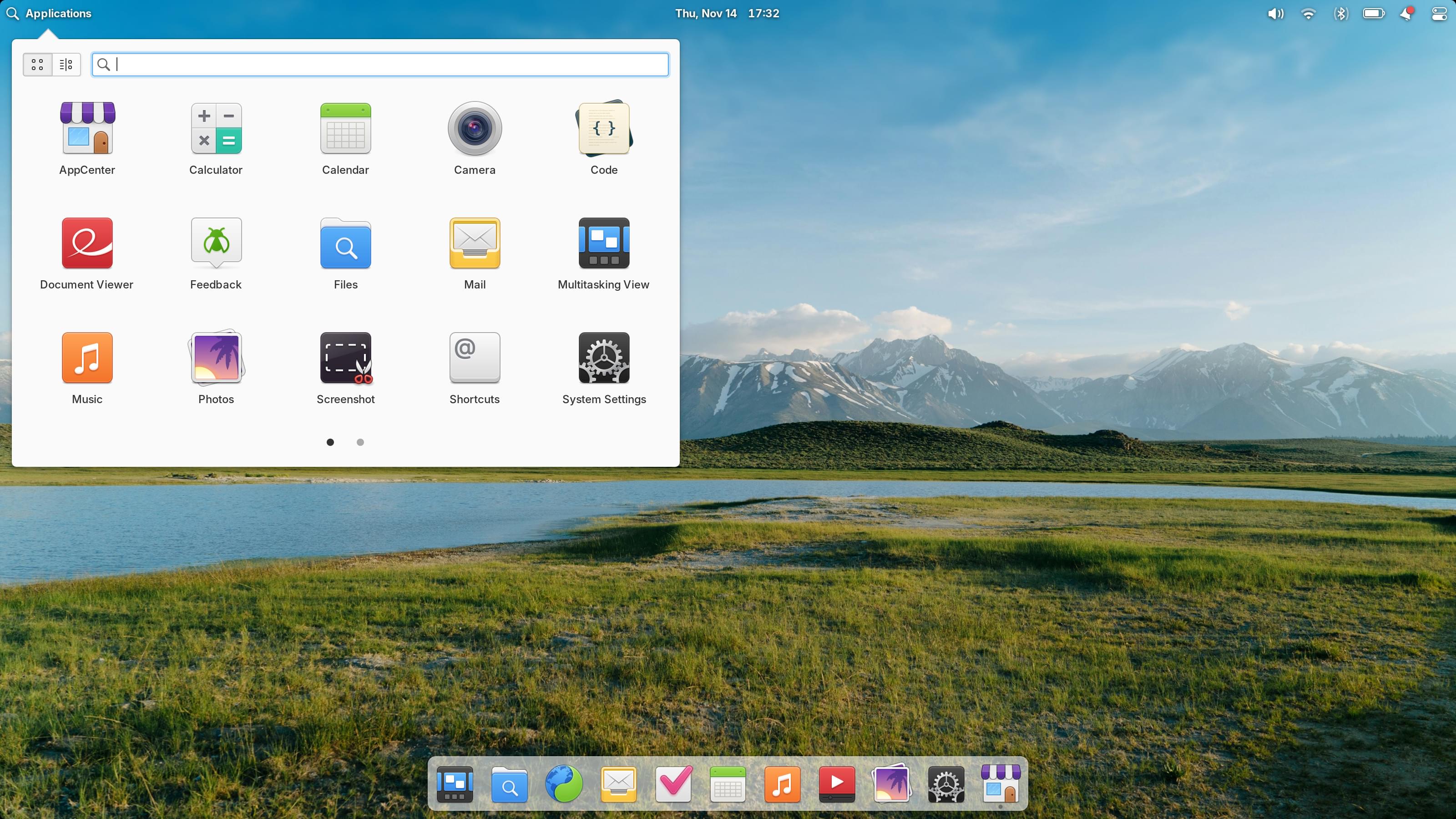

While Linux, which was created in 1991 by Linus Torvalds, has apparently made solid improvements for everyday users in the last few years, it is still a bit rough around the edges. As of the beginning of 2019, Linux is still not for everyone. That said some folks are continuing the work to change that. When I think of a non-technical user wanting to run Linux, in my eyes the best bet seems to be the work of the folks running a version of Linux (known as a “distribution” or “distro”) called elementary OS, which is aimed directly at replacing Mac and Windows for everyday computer users.

(I should note that I haven’t tried Elementary OS yet; I’ve stuck with a different “distribution” called Kubuntu, which fits me well.)

There are many different distributions of Linux, most of which can be paired with a number of “desktop environments”… it gets nerdy real quick with this stuff. But tl;dr users get a ton of choices, which protects them further from the tyranny of one team of developers or one company. Crucially, switching isn’t super hard– for example, if I had to, I’m confident I could switch from Kubuntu to Elementary in a few hours. Most of these distributions take user privacy very seriously, and none of them are much like the “giants” Manjoo warns us of.

One night out at a bar with a friend, early on in my Linux experiment, I started breathlessly talking about how I’d made the switch and maybe preaching about how great it was. My friend finally got a question in: “Why should I switch?” In my mind I thought he was asking, essentially, “What’s Linux’s killer app?” or more basically, “what can I do on Linux that I can’t do on, say, MacOS?”

I admit I was stumped. (There are some things Linux does better than MacOS, no philosophical sales pitch needed, but in my experience these are mostly things having to do with running and/or compiling code from source.)

What it’s like to use Linux

If Linux has an underlying mantra, it’s that, for better or worse, you’re running your computer (in the literature, users run Linux, rather than use it). You can (and very well might) accidentally render your computer unusable (known as “bricking”). There’s a bit of a learning curve. But this also means you’re more free to make it work, look, and act the way you want. Want the latest, cutting edge version of software all the time? Use a “rolling” distro like Arch Linux. Have old hardware? You’ve got XFCE. There’s a whole subbreddit full of users showing off their aesthetic tweaks, which were and still are strikingly diverse to me, each customized to the users liking and workflow. As Tim Wu writes, some technology should be a little demanding. Once you get the hang of Linux, and you know which compatible apps you like, both setting up and using Linux can be very smooth.

[Plasma] i have mastered the moves from r/unixporn

I’ve also found a certain humility in the Linux community and in the greater free software community. Rarely is anything advertised as “it just works” – there’s no economic incentive for such claims. So when things aren’t quite right, support is generally easy to find online – without much defensive posturing as preamble – and other users are generally very helpful and invested and know they’re probably just as likely to learn a tip or trick or new way to do things from you as they are to teach you. And if something really isn’t right in the software, there are ways for non-developers to describe bugs, problems, or feature requests for developers, add to a piece of software’s documentation, or, if able, change the code themselves and propose that the change be adopted, which is how I made the scroll bars on Mastodon’s web frontend slightly wider.

Some other benefits of using Linux and free applications: Once I got things set up well, it’s been pretty stable; but if something ever does go wrong, re-building my operating system from nothing (or more specifically, a downloaded file burned on to a USB stick) is pretty easy once you’ve done it a few times. Software update notifications are also very unobtrusive (something that was always annoying when using MacOS, particularly in the last few years) – Linux gets out of my way. And Linux distros generally respect user privacy, which, granted, apparently draws a sharper contrast with Microsoft Windows 10 than MacOS at this point.

We are proud to have played our small part in @NASAInSight's #MarsLanding. Congratulations @NASA! pic.twitter.com/W06g3VGmH9

— KDE Community (@kdecommunity) November 27, 2018

All that said, I’m not quite ready to say Linux is for everyone…. though I should push myself, in the future, to enumerate the reasons more specifically. At this point it’s mostly: Foreignness of the command line, loss of applications users rely on, and maybe some hardware compatibility. When I think about this question I think about whether I could install Linux on my parents’ computers. Granted, most of the issues I foresee are the same types of issues I’d anticipate if they suddenly jumped from Mac to Windows, for example.

At this point my strongest pitch to switch is the ethics

At this point, if forced to give one answer to the question of why some users should switch to Linux, it’s that it allows you (or forces you) to be a more conscientious and ethical consumer of technology. As Manjoo writes,

But you don’t have to wait for politicians to weigh in. Your choices as a consumer matter, too – and for a better, healthier tech industry … The lesson of the last decade is that our private tech choices can alter economies and societies. They matter. And they matter most in the mindless rush, when everyone seems to be jumping on board the latest new thing, because it’s in these heady moments that we lose sight of the precise risks of turning ourselves over to tech.

Yes, it’s an adjustment: you’ll almost certainly have to switch some apps. Yes, it may or may not be as smooth as MacOS for a while. No, you can’t use Photoshop. But it’s fun to take a wrench to your computer every once in a while, or at least know you can. Nobody asks to be buried with their iPad.

Mastodon

In 2018 I also used Mastodon, a open-source, federated social network, more than I did in 2017. Mastodon fits Manjoo’s maxims well: It’s not a giant, and it has grown slowly over the last few years (to the confusion of some observers who are used to tech companies and social networks either exploding with exponential growth right away, or quickly die off). To understand its business model, if it can be thought to have one, you have to understand a bit about its federation work. The simplest explanation I can provide is that when you “join” Mastodon you’re really joined an “instance” of Mastodon. Anyone can start and run an instance, and they can be large or small, general, or specific to an interest, like humor, free software, being a furry, etc. By default users all instances of Mastodon can talk to each other, though instance admins or individual users can block whole instances. And most instances are crowd-funded by their users (here’s the Patreon of the instance I’m on).

I still use Twitter and other social networks of course, but in 2018 I came to really enjoy using Mastodon.

What about ditching the giants altogether?

Thanks to Linux I’ve shaved my Apple use down to my iPhone, and cut my last ties to Microsoft by no longer needing Office. Mastodon is a cool social network, but it doesn’t replace other networks of friends you’ve made. And while I use Firefox and DuckDuckGo more, I still use Google for email, mostly for the security and anti-spam features, and simple inertia, and I use Chrome on Linux to watch Hulu and Netflix. This is all to say that I didn’t make all of my tech usage as ethical as possible in 2018. But I think I made some good steps.

Update as of November 2019

Still using Linux (specifically, Kubuntu 18.04) on my Oryx Pro! I’ve collected a lot of my notes on how I set up and use Linux over in this “Docs” site.

Also, I now use Firefox (v 70.0.1) for everything, including watching videos on Hulu and Netflix. Still using Google for email and my calendar though.

I’m also looking for decentralized options for things like real-time, encrypted messaging. There’s no clear front-runner for that right now as far as I can tell, but three promising options are Matrix/Riot, Cwtch, and XMPP with OMEMO. In reality I still use Wire and Signal, which are still both centralized and slightly problematic for different reasons.