Back in May, I was reading over SecureDrop’s documentation and its corresponding GitHub Issues. (If you don’t know, SecureDrop “is an open-source whistleblower submission system that media organizations can use to securely accept documents from and communicate with anonymous sources.” It’s maintained by the Freedom of the Press Foundation.)

For journalists, the actual running and maintenance of a SecureDrop “instance” involves generating and storing quite a few strong, unique passphrases. In fact, the documentation has a page dedicated to passphrases, which first summarizes all of the passwords users need to create and keep track of.

It’s my understanding that, of these passphrases, the ones that actual humans need to remember are used to protect Tails persistent storage volumes. Basically, SecureDrop makes heavy use of an operating system called Tails. The features of Tails, while awesome, are a bit beyond the scope of this blog post. What we need to know is that: if you want to any files you create or download while using Tails to exist after shutting down Tails, you need to save them in a volume or partition called “persistent storage”. This volume is encrypted with a passphrase that the user enters when setting up the volume. Given SecureDrop’s threat model, we want these persistent storage volumes to be well protected in case the USB drives that Tails is installed on get compromised.

I spotted two issues related to passphrases that I felt able to contribute to: “Explain how to generate a diceware passphrase #332” and “Provide guidance on how strong the Tails admin password should be #335”.

What the documentation said before my submitted changes

At the time, the Tails setup page in the documentation advised users to use dice to create passphrases, linking to an Intercept article.

Each Tails persistent volume should have an unique and complex passphrase that’s easy to write down or remember. We recommend using Diceware passphrases.

We can see the two GitHub issues right here in this paragraph: First, it only suggests one method to generate these passphrases, which involves using physical dice. And second, it doesn’t say how strong the passphrases need to be.

Is KeePassXC’s passphrase generator acceptable method for SecureDrop users to generate passphrases?

Let’s take these in order. How else might SecureDrop users create strong, random passphrases?

Tails comes with a password manager called KeePassXC. As you might imagine, KeePassXC can generate random passphrases. I figured it was worth at least suggesting in an edit (GitHub calls these suggested edits “pull requests”, often abbreviated as “PR”) that users be able to trust KeePassXC’s random passphrase generator. Not everyone wants to find and roll dice to make a passphrase!

This idea seems to have been uncontroversial and well received!

How strong should the passphrases be?

The next question in re-writing these recommendations in the docs was how strong to recommend these passphrases should be. (I was a little surprised that there wasn’t more guidance on this!)

To answer that question, we need to look at how we expect these passphrases to be created: either by using dice or, now, by using KeePassXC. Luckily, both of these methods use the same list of words to choose from. The word list is called the “EFF long list” and, notable for our purposes, it has 7,7776 words on it.

Now that we can assume a constant list length of 7,776, our real questions becomes: how many words should each unique passphrase be?

An initial, conservative guess

In my initial pull request, I conservatively suggested 7-word passphrases (which gives about 90 bits of entropy). I figured that was a decent balance between usability and security (OK, maybe erring more on the security side). I figured we could hash out the exact number in the comments of the pull request on GitHub – what was important was getting the pull request going.

Thankfully, David Huerta, a Freedom of the Press digital security trainer, answered a few of our questions:

I haven’t yet seen solid evidence showing that 7 words is necessary for Tails persistent storage passphrases. Most password cracking models that I’ve explored don’t seem to go into detail on whether or not they take things like the speed of a hashing function into account. If LUKS’s encryption scheme would have any mitigations that would slow password cracking attempts, as algorithm implementations in some password managers do, for example (https://security.stackexchange.com/a/137307, “Bruteforcing the master password”), then it may be that a shorter passphrase would be fine, and I think it’s useful to explore that possibility.

Based only on my anecdotal evidence (but in this case anecdotes from newsrooms) the longer a passphrase is, the more difficult it will be to memorize. Without going into detail I’ve seen journalists use other means to store their long passphrases. Easier-to-remember passphrases may make those other means less necessary.

This told me a few things. First – and I maybe should have know this beforehand – the Tails persistent storage volumes use LUKS disk encryption. Second, as expected, journalists are humans and there is indeed a trade-off between security and convenience here. Was 7 words too many? Would journalists forget them too often, or resort to poor security practices to remember them? David provided a route to a better answer by asking what mitigations LUKS has to slow cracking attempts.

Wait, remind me what we’re doing here

Ultimately, we want to figure out how many guesses at the passphrase an attacker can make in a second. The mitigations Huerta references are steps that LUKS takes to slow these guesses down. For example, if we can slow it down such that it takes, say, 1 full second for an attacker to make a guess, it’ll take 11 days for them to make a million guesses. It’ll take 31 years to make a billion guesses.

Here’s a metaphor for us to think about. Let’s say you’ve got a safe that requires a combination to open. To keep it simple, let’s say the dial goes from 1 to 10 and the combination is just 2 numbers. 10 squared is 100, so there are only 100 possible combinations to open the safe. In this case, an attacker could do what we might call a “brute force” attack, where they start with 1-1 and work their way up to 10-10. If it takes 3 seconds to try a combination, the attacker will get through all of them in 5 minutes (and on average, will try your combination about halfway through, so only 150 seconds after their first attempt).

Not great! What are some ways we could make it take longer? First, we could make the dial bigger (like 1 to 100). We could also make the safe take 3 or 4 or 5 numbers instead of just 2 (kind of like making a password longer).

Another way would be to change the safe/dial in such a way that it takes longer than 3 seconds to try a combination. For example, what if the dial required you to turn the dial a few times between attempts (or between individual numbers). If we , say ,tripled the amount of time it takes to make a guess, we’ve tripled the time to crack the safe.

To tie this back to the technological issue at hand, in our LUKS encryption situation, we can think of the LUKS encrypted volume as our safe. We’re looking to see how long it takes for an attacker to find out if a given password is correct or incorrect. Is it a negligible amount of time? Does LUKS have some protections in place to slow guessing down? How many times do you have to turn the dial to make one guess?

Learning about Tails and LUKS

To find out, I first had to make an encrypted volume, just like a SecureDrop admin would (obviously mine is just for testing purposes). As I replied on Github:

I took this as a challenge to do a little investigating. I installed and started up Tails (first time!) following these instructions. I then created a persistent storage partition (using a trivial passphrase) following these instructions. In both cases, I was attempting to do what I’d assume a regular SecureDrop user would do, following current documentation.

Next, we need a tool to tell us about the protections on this LUKS “safe”.

Then I went off-script, and I set an admin password for Tails and installed cryptsetup from the tar file linked from this Gitlab repo (installing via

sudo apt install cryptsetupwas giving me issues, I assume because its Tails). I then ransudo ./cryptsetup luksDump /dev/sdb2to learn more about our new encrypted partition. Here’s what it output:

(In other words, I asked for more information about the safe I had just created and its lock. And here’s what I got.)

LUKS header information for /dev/sdb2

Version: 1

Cipher name: aes

Cipher mode: xts-plain64

Hash spec: sha256

Payload offset: 4096

MK bits: 512

MK digest: 42 83 6b 5b f7 86 c4 43 9f a4 3a e0 88 7e 96 dd bb f1 e7 1b

MK salt: 2d a6 f7 26 07 ee b5 6d 7e 88 c1 4b ac 62 4e 7e

74 d5 61 69 df f2 7b 4b 50 d2 71 ca 32 bb 42 82

MK iterations: 113580

UUID: c2874e1b-fbf0-49ff-85b8-ec4c17de2047

Key Slot 0: ENABLED

Iterations: 1820444

Salt: 0a 38 61 15 4b b6 39 b5 45 c4 a7 22 59 59 2c 34

65 cc d0 73 6a 57 58 8c 6a bf 24 97 00 7f 43 f1

Key material offset: 8

AF stripes: 4000

Key Slot 1: DISABLED

Key Slot 2: DISABLED

Key Slot 3: DISABLED

Key Slot 4: DISABLED

Key Slot 5: DISABLED

Key Slot 6: DISABLED

Key Slot 7: DISABLED

This gives us a few useful pieces of information about our “safe”. First, that this fresh Tails persistent storage volume uses LUKS version 1. I’m pretty sure that LUKS version 1 uses PBKDF as its key derivation function.

Next, I focused on the “Hash spec”: “sha256”. I guessed that that means that the partition uses PBKDF2-SHA256 to hash the passphrase (the “internal hash function” is HMAC-SHA-256).

Finally,

the other number we’re interested in is number of iterations… I’m not sure if that’s the 113,580 number or 1,820,444. If I had to guess I’d say “MK” stands for “master key”, which is not the passphrase the users sets, so for our purposes, we’re more concerned with the ~1.8 million number. (Obviously neither are round numbers, so my guess is that the Tails GUI uses a time-based benchmark to set this value?)

For our safe metaphor, this is information about the safe and its lock I made when I created my test LUKS volume. To see if a password is correct, users (or attackers) much complete 1.8 million iterations (or, turns of the dial) to find out if it’s the correct password (combination)!!

That might sound like a lot, but my same laptop can do about 1,736,052 iterations per second on this type of “dial”. (Maybe we can imagine the attacker with a gasoline-powered dialer?) As an aside, I don’t think it’s a coincidence that these numbers are relatively close: It’s likely that Tails/LUKS used a one-second benchmark from my laptop when it say the 1.8 million number.

Let’s call it a round 1 second per guess.

Now let’s look at a straight-word example passphrase/combination. If we make a passphrase (a password made up of words rather than characters and numbers) with words from the EFF list of 7,776 words, like “crook-pushover-faceted”, it’s as if the safe’s dial has 7,776 numbers on it. Awesome – the bigger the dial, the larger number of possible combinations, the more “space” the attacker has to brute-force through. Now let’s say that the passphrase is 3 words long. At one second per guess , it’d take an attacker using my laptop about 156 centuries to guess them all. If the passphrase is 4 words long (“expansive-unison-carport-latter”), this number jumps to 121,500 millenia.

A slightly more realistic estimate

Of course, an attacker trying to break into a Tails USB drive used by a SecureDrop user is likely going to be using a bit more computer power than a 5-year-old laptop.

Luckily, 1Password held a passphrase-cracking contest back in 2018 with similar goals to ours:

Our (1Password’s) goals in offering these challenges is to gain a better sense of the resistance of various types of user Master Passwords to cracking if 1Password data is captured from a user’s device.

Even more luckily, the parameters of their challenge are similar to the LUKS defaults I found on Tails: They published a series of hashes derived from 100,000 rounds of HMAC-SHA256 on a 3-word passphrase from their word list (about 18,000 words). The (eventual) winners say they used 21 NVIDIA cards worth of computing power and sustained an average speed of 209.85 kH/s., or 209,850 guess per second. Given our formula above, and for conservative sake, maintaining the 100k iterations of the contest, that’s 1 / 209850 * 7776**4 / 60 / 60 / 24 / 365 or 552 years to get through the entire space of a 4-word passphrase from the EFF long list. 3 words takes 25 days.

Thus, 3 words is a little dicey, 4 feels better…

If we 20x the assumed guesses per section to 4.2 million guess per second, we get 27.6 years for 4 words, 214 millennia for 5 words.

In the end, I stuck by my recommendation of 7 words. I figured I didn’t want to be the reason one of these encrypted drives gets cracked. I think you’d want more user stories to make a call on whether the trade-off between security and convenience is worth knocking this down to 6 or 5 words. And obviously it’d be easy to tweak the number of the recommendation in the documentation. I’m proud that I got the ball rolling, and was able to do a little light forensic work that I hope isn’t too off-the-mark.

The end result

You can now read my contribution to the docs on the current “Passphrases” page. I’ll recreate it below as well.

How to Generate a Strong, Unique Passphrase

We recommend using a unique, 7-word passphrase for each case described above. You can create these passphrases either by using physical dice or with KeePassXC, a password manager included with Tails.

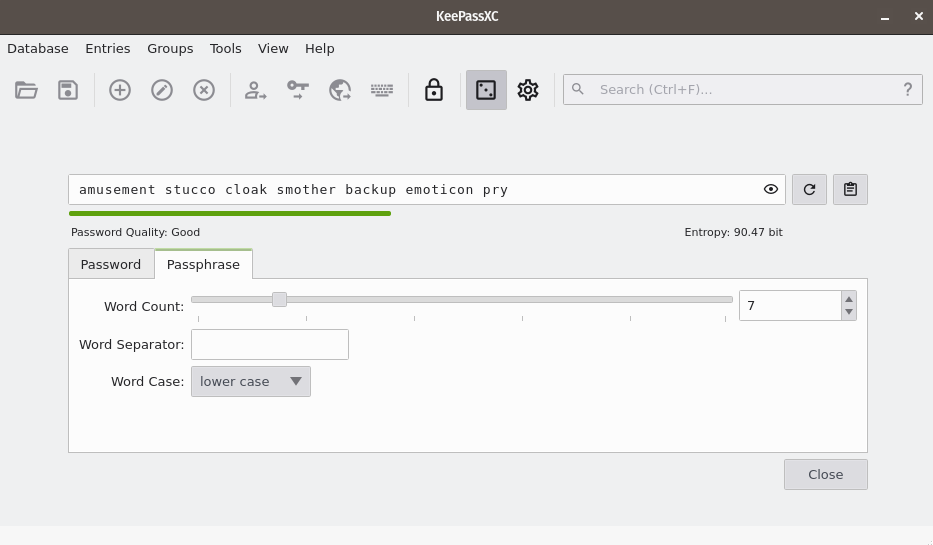

Using KeePassXC to Generate a Passphrase

To create a random passphrase using KeePassXC, launch the application, then click the dice icon. Then click the Passphrase tab and set the Word Count to 7. You can optionally set a Word Separator, for example a space or hyphen.

2023 Update

This change likely changes all of the math above. Hopefully a shorter passphrase can provide the same amount of protect for SecureDrop users!